The Greatest African American and Afro-American Martial Artists in History

In Bizarre and Unusual, Customs and Traditions, Edwardian Era, Middle Ages, Military, Renaissance on March 25, 2014 at 4:34 pm

By Ben Miller

When asked to recall a great martial artist of African descent born in the Americas, the average person is likely to mention a twentieth-century boxer such as Joe Louis, or a more recent exponent of the Asian martial arts, such as Jim Kelly. Or, those of the younger generation might name the modern mixed martial arts competitor Anderson Silva, regarded by some as the greatest pound-for-pound fighter of all time.

What many do not know is that in centuries past, some of the greatest practitioners of European martial arts were of African descent.

Although Africans brought a number of their own indigenous techniques with them to Europe and the Americas (as can be read about here), they also sometimes trained in, adopted, and excelled at European swordsmanship—also known as classical and historical fencing.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, it was even possible (albeit difficult) for a person of African descent to achieve renown to such a point that they would be revered, and even sought for instruction, by whites—and the historical record shows that such was the case for multiple individuals.

This is not to in any way minimize the oppression and ordeals that African Americans and African Europeans endured in the past. Rather, it is a testament to the extraordinary skill, ability, dedication, and perseverance of these individuals, which allowed them to triumph–at least as much as was possible–over the prejudices of their time, and ascend to the highest ranks of martial achievement.

An early instance of one such person can be found as early as 1733, when the following advertisement appeared in a southern Colonial newspaper, informing the public about a runaway slave or indentured servant:

“Run away, from Mr. Alex. Vanderdussen’s Plantation at Goose-Creek, a Negro Man named Thomas Butler, the famous Pushing and Dancing Master.” – South-Carolina Gazette (Whitmarsh), May 19 to May 26, 1733.In eighteenth century terminology, to “Push” was to launch an attack with the smallsword, a fact which confirms that Thomas Butler was a fencing master—and one who had achieved some degree of fame, at least on a local scale. Butler was apparently so esteemed that in July of 1734, his former master was impelled to post the following additional notice:

“Whereas Thomas Butler, Fencing Master, has been runaway these two years since, and has been entertained by several gentlemen about Ferry who pretend not to know that he had a master, this is therefore desired that they would not do the like in the future…” – South-Carolina Gazette, July 20, 1734These passages are all the more remarkable when one considers that they are the earliest known reference to a fencing master in the American South—the next being Edward Blackwell, who in 1734 posthumously published his treatise on the art of fencing. Although not much else is known about Thomas Butler, the above passages prove that as early as the 1730s, it was not impossible to achieve fame and esteem as a black martial artist (and instructor) in white society. This article will profile three of the greatest such individuals—the Chevalier de Saint Georges, Jean Louis-Michel, and Basile Croquere.

Historical Background

As far back as the age of antiquity, there is evidence of martial artists of African descent testing their abilities in Europe. In ancient Rome, numerous African gladiators, mainly from Ethiopia, fought in the arenas made famous at Pompeii and the Coliseum. Most were, of course, brought to Rome as slaves; however, some gladiators were able to win their freedom due to their celebrated fighting ability, and even continued to fight in the arenas. Although a period image of African gladiators wielding swords could not be found for this article, on the right is a mosaic depicting an Ethiopian retiarius, or net-and-trident-wielding gladiator, currently housed at the Musée Granet, Aix en Provence, France. Likewise, below is a photograph of two ancient roman terracotta statues, probably from the 2nd or 1st century BC, depicting two African pugilists appearing to wield the cestus, a fighting glove sometimes used in pankration. Made of leather strips, cesti were sometimes filled with iron plates or fitted with blades or spikes, and could be devastating weapons.

As far back as the age of antiquity, there is evidence of martial artists of African descent testing their abilities in Europe. In ancient Rome, numerous African gladiators, mainly from Ethiopia, fought in the arenas made famous at Pompeii and the Coliseum. Most were, of course, brought to Rome as slaves; however, some gladiators were able to win their freedom due to their celebrated fighting ability, and even continued to fight in the arenas. Although a period image of African gladiators wielding swords could not be found for this article, on the right is a mosaic depicting an Ethiopian retiarius, or net-and-trident-wielding gladiator, currently housed at the Musée Granet, Aix en Provence, France. Likewise, below is a photograph of two ancient roman terracotta statues, probably from the 2nd or 1st century BC, depicting two African pugilists appearing to wield the cestus, a fighting glove sometimes used in pankration. Made of leather strips, cesti were sometimes filled with iron plates or fitted with blades or spikes, and could be devastating weapons.

As early as the late middle ages, people of African descent began appearing in European treatises on swordsmanship and the martial arts, such as the book of Hans Talhoffer (1467), plates of which are featured below:

Above: Plates from the work of Hans Tallhoffer (thanks to Michael Chidester for locating these images)

Above: A sickle fencer, clearly of African descent, pictured in Paulus Hector Mair’s De arte athletica, published in Augsburg, Germany, ca 1542. Source: http://infinitemachine.tumblr.com

Above: A fencer of African descent, wielding an early rapier (or “sidesword”) pictured in Paulus Hector Mair’s De arte athletica, published in Augsburg, Germany, ca 1542. Source: http://www.hammaborg.de/de/transkriptionen/phm_dresden_2/05_rapier.php

Some of [the African servants], who have been bred up amongst the Portugals, have some extraordinary qualities, which the others have not; as singing and fencing. I have seen some of these Portugal Negres, at Colonel James Draxes, play at Rapier and Dagger very skillfully, with their Stookados [Stoccatos], their Imbrocados, and their Passes: And at single Rapier too, after the manner of Charanza [Carranza], with such comeliness; as, if the skill had been wanting, the motions would have pleased you; but they were skilful too, which I perceived by their binding with their points, and nimble and subtle avoidings with their bodies, and the advantages the strongest man had in the close , which the other avoided by the nimbleness and skillfulness of his motion. For, in this Science, I had bin so well vers’d in my youth, as I was now able to be a competent Judge. Upon their first appearance upon the Stage, they march towards one another, with a slow majestick pace, and a bold commanding look, as if they meant both to conquer and coming neer together, they shake hands, and embrace one another, with a cheerful look. But their retreat is much quicker then their advance, and, being at first distance, change their countenance, and put themselves into their postures and so after a pass or two, retire, and then to’t again: And when they have done their play, they embrace, shake hands, and putting on their smoother countenances, give their respect to their Master, and so go off.Ligon’s account provides evidence that despite their low social status, people of African descent living in the American colonies were sometimes allowed—even encouraged—to train with various weapons, including the rapier and dagger, and became skilled at multiple styles—including Italian rapier fencing, as well as the profound system of Spanish swordsmanship (La Verdadera Destreza) founded by Jerónimo de Carranza.

– Richard Ligon, A true & exact history of the island of Barbados, 1657.

Colonists of African descent also undoubtedly learned from less savory channels such as piracy; an estimated one-third of pirates during this period were black, and in such company, knowledge of swordsmanship was paramount. The following passage, culled from Captain Johnson’s General History of the Pirates (1728), gives rise to the possibility that black members had access to sword instruction:

“[Pirate Captain] Misson took upon him the Command of 100 Negroes, who were well disciplin’d, (for every Morning they had been used to perform their Exercise, which was taught them by a French Serjeant, one of their Company, who belong’d to the [ship] Victoire)…”During the early 1700s, a number of swordsmen of African descent also fought as gladiators in the British colonies. Although these highly ritualized combats took place in locations as remote as Jamaica, Barbados, and rural Ireland, during the seventeenth century the most popular setting for such fights was undoubtedly the infamous “Bear Garden” in Southwark, London. In 1672, a Frenchman named Josevin de Rocheford visited the Bear Garden and observed:

“We went to the ‘Bergiardin’, where combats are fought by all sorts of animals, and sometimes men, as we once saw. Commonly, when any fencing-masters are desirous of showing their courage and great skill, they issue mutual challenges, and before they engage parade the town with drums and trumpets sounding, to inform the public there is a challenge between two brave masters of the science of defence, and that the battle will be fought on such a day.”What followed these processions was violent and often gruesome. On the appointed day, to the sound of trumpets and beating drums, the two combatants would ascend the stage, strip to their chests, and, on a signal from the drum, draw their weapons and commence fighting. The combat would continue until one man conceded, or was unable to continue. In de Rocheford’s account, the combatants continue fighting while enduring horrific wounds, including severed ears, sliced-off scalps and half-severed wrists. Bouts occurred with different types of weapons, including longsword, backsword, cudgel, foil, single rapier, rapier and dagger, sword and buckler, sword and gauntlet, falchion, flail, pike, halberd, and quarterstaff. Although such fights were not intended to end in death, the wounds received were often serious enough to incur it.

At least a small number of these gladiators are recorded as being of African descent. One of the earliest known instances was in May of 1701, when “George Nervil Turner, a Black, Master of the Small Sword,” who had “fought several Prizes,” and “William Tompson, a Black…Master of the Science of Defence,” appeared at the Bear Garden in London, challenging several other gladiators to a contest with sharp weapons. It was announced that “all four do intend to fight a double Prize, James Harris and William Page against the two Blacks…by reason each man doth intend to exercise the six usual Weapons.”

Another such example was “Thomas Phillips, the Black from Jamaica, Master of the Noble Science of Defence,” who fought in at least several public contests between 1724 and 1725. Many of these public challenges were racially charged (a common feature of the period), as can be seen in the following specimen, published on September 14, 1724, and fought between Phillips and a white Englishman named Robert Carter:

During the early 18th century, an English fencing treatise entitled “The Art of Defence,” printed and sold by one “John King”, was published containing several plates in which black fencers demonstrated various fencing techniques:

Above: Illustration of a black fencer making a “pass in tierce with the knuckles up,” while checking the adversary’s blade with his unarmed hand. Source:www.truefork.org.

Also at this time emerged one of one the greatest fencers of all time, who just happened to be of African descent.

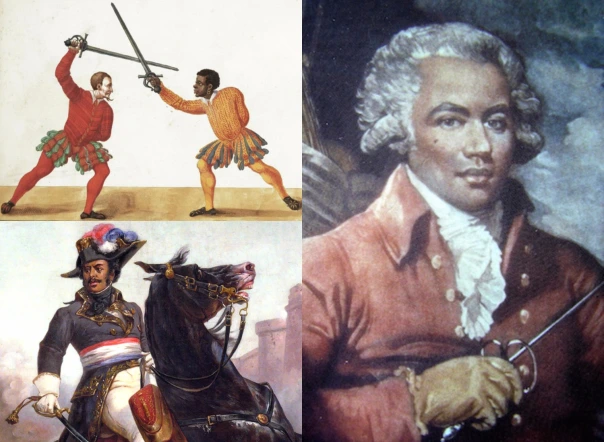

The Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745–1799) was born in Guadeloupe, in the Caribbean, the son of George Bologne de Saint-Georges, a wealthy planter, and an African slave named Nanon. Although his father also had many white children, he took a special liking to Joseph, and in 1753 took his son, age seven, to France, where he began his education in a variety of arts including fencing.

According to the son of the fencing master La Boëssière, “At 15 his [Saint-Georges’] progress was so rapid, that he was already beating the best swordsmen, and at 17 he developed the greatest speed imaginable.”He was still a student when he publicly defeated Alexandre Picard, a renowned fencing-master in Rouen who had foolishly referred to Saint-Georges as “Boëssière’s mulatto.” Heny Angelo, son of the famous Domenico (and a highly reputed fencing master in his own right) often went to fence with Saint-Georges while in Paris, and wrote about him in his memoirs:

“No man ever united so much suppleness with so much strength. He excelled in all the bodily exercises in which he engaged…He was a skillful horseman and remarkable shot; he rarely missed his aim when his pistol was once before the mark…but the art in which he surpassed all his contemporaries and predecessors was fencing. No professor or amateur ever showed so much accuracy and quickness. His attacks were a perpetual series of hits; his [parry] was so close that it was in vain to attempt to touch him; in short, he was all nerve.”Angelo also related some details about Saint-Georges in the following anecdote, regarding an episode wherein the two crossed blades:

“It may not be unworthy of remark that from his being much taller, and, consequently, possessing a greater length of lunge, I found that I could not depend upon my attacks unless I closed with him. The consequence was, upon my adopting that measure, the hit I gave him was so ‘palpable’ that it threw open his waistcoat, which so enraged him that, in his fury, I received a blow from the pommel of his foil on my chin, the mark of which I still retain. It may be remarked of that celebrated man that, although he might be considered as a lion with a foil in his hand, the contest over he was as docile as a lamb, for soon after the above engagement, when seated to rest himself, he said to me: ‘Mon cher ami, donnez-moi votre main; nous tirons tous les jours ensemble.’”Although there are too many anecdotes about Saint-George’s prowess to recount here, one of the best comes from Alfred Hutton, and occurred in Dunkirk.

Saint-Georges was attending a party with a large number of ladies, when a Captain of the Hussars began boasting of his own skill in fencing—oblivious to the identity of Saint Georges. The latter calmly asked the captain, “That is interesting…but did you ever happen to meet with the celebrated Saint-Georges?” The Captain responded: “”Saint Georges? Oh yes; I have fenced with him many a time. But he is no good; I can touch him just when I please.” Whereupon Saint-Georges challenged the Captain to a bout at foils on the spot. Hutton’s account continues:

“The Captain, seeing that he is opposed to a man much older than himself, is inclined to treat him with contempt, when the veteran fencer calmly turns to the ladies and asks them to name the particular buttons on the gentleman’s coat which they would like him to touch. They select half a dozen or so.Saint-Georges also became a respected music composer, and became the instructor of Queen Marie Antoinette. In her diary, the Queen referred to Saint-Georges as her “favorite American.”

The pair engage. The famous swordsman plays with his man for a few minutes for the benefit of his audience, and then proceeds to hit each of the named buttons in rapid succession, and finishes by sending the foil of his vainglorious enemy flying out of his hand, to the great delight of the ladies, and the discomfited Captain is so enraged that he wants to make the affair a serious one [a duel] there and then. His victorious opponent corrects him with: “Young gentlemen, such an encounter could have but one ending. Be advised; reserve your forces for the service of your country. Go, and you may at last tell your friends with truth that you have crossed foils with me. My name is Saint Georges.”

Sketch entitled “St. Georges and the Dragon,” depicting Saint-Georges boxing. Source: http://theprintshopwindow.wordpress.com/2013/04/16/a-truly-british-art-images-of-pugilism-in-georgian-caricature/

“Early in July [1789], walking home from Greenwich, a man armed with a pistol demanded his purse. The Chevalier disarmed the man… but when four more rogues hidden until then attacked him, he put them all out of commission. M. de Saint Georges received only some contusions which did not keep him from going on that night to play music in the company of friends.”The Journal General de France, on February 23, 1790, also reported that: “the Chevalier was peacefully walking to Greenwich one night where he was going to make music in a house where he was awaited when he was suddenly attacked by four men armed with pistols. Nevertheless he managed to drive them off with the help of his stick.”

Saint-Georges meets a rival fencing master who has challenged him to a duel, under L’arche Marion. Source: Source: Wikimedia Commons

General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, painted by Olivier Pichat. Source:http://s236.photobucket.com/user/DeeOlive/media/GeneralDumas_zps10105513.jpg.html

Although Saint Georges passed away in 1799, his name and image is venerated among classical and historical fencers throughout the world.

Jean-Louis Michel

“The founder of the modern French school of swordsmanship, and the greatest swordsman of his century, was a mulatto of San Domingo, that famous Jean Louis, who in one terrible succession of duels, occupying only forty minutes, killed or disabled thirteen master-fencers of that Italian army pressed into service by Napoleon for his Peninsular campaign.” – Lafcadio Hearn, 1886Jean-Louis was born in Haiti (then Saint-Domingue) in 1785, the son of a French fencing master. Later, he served as a soldier in Napoleon’s army.

His most famous exploit as a duelist was a regimental “mass” duel that took place near Madrid, Spain, in 1814. French soldiers from the 32nd Regiment and Italian soldiers from the 1st Regiment quarreled. Within 40 minutes, Jean-Louis killed or disabled thirteen Italian fencing masters in succession:

The regiments were assembled in a hollow square on a plain outside Madrid. At its center was a natural elevation forming a platform where, two at a time, 30 champions would duel for the honor of 10,000 men. As the premier fencing master of the 32d Regiment, Jean-Louis was the first up. His opponent was Giacomo Ferrari, a celebrated Florentine swordsman and fencing master of the First Regiment.

Drums rolled. The troops were ordered to parade rest, and as they slammed down the butts of their muskets in unison, the earth shook. Jean-Louis and Giacomo Ferrari stepped onto the fencing strip, each stripped to the waist to show that they wore nothing that would turn a thrust. An expectant silence filled the air as every eye was fixed on the two masters…

The fencing masters crossed swords and the bout began. Ferrari took the offensive, but Jean-Louis followed all his flourishes with a calm but intense attention; every time Ferrari tried to strike, his sword met steel. With a loud cry Ferrari jumped to the side and attempted an attack from below, but Jean-Louis parried the thrust and with a lightning riposte wounded Ferrari in the shoulder. “It is nothing, start the fight again!” cried Ferrari, getting back to his feet. Jean-Louis’ next thrust struck home, and Ferrari fell dead.

Jean-Louis wiped the blood from his blade, resumed his first position, and waited. His battle had only begun. The victor in each bout was to continue until he was injured or killed, and Jean-Louis still faced 14 swordsmen of the 1st Regiment, all of them eager to avenge their comrade.

Another adversary came at him. After a brief clash, Jean-Louis lunged and, while recovering, left his point in line. Rushing at him, his opponent was impaled. A second corpse lay at the French master’s feet.

His third opponent, a taller man, attacked fiercely, with jumps and feints, but Jean-Louis’ point disappeared into his chest, and he fell unconscious.

The next man approached. The regiments watched in fascinated silence. They were accustomed to the wholesale music of slaughter: the booming of artillery, the bursting of shells, the rattle of musketry, the clash of sabers. All are impressive, but none so keenly painful as the thin whisk of steel against steel as men engage in single combat. As one contemporary observer wrote, “it goes clean through the mind and makes the blood of the brain run cold.”

After 40 minutes only two Italian provosts were left awaiting their turn, pale but resolved. A truce was called, and the colonel of the 32d approached Jean-Louis.– Paul Kirchner, The Deadliest Men

“Maitre,” he said, “you have valiantly defended the regiment’s honor, and in the name of your comrades, and my name, I thank you sincerely. However, 13 consecutive duels have taken too much of your body stamina. Retire now, and if the provosts decide to finish the combat with their opponents, they will be free to do so.”

“No, no!” exploded Jean-Louis, “I shall not leave the post which has been assigned me by the confidence of the 32d Regiment. Here I shall remain, and here I shall fight as long as I can hold my weapon.” As he finished his statement he made a flourish with his sword, which cut one of his friends on the leg. “Ah,” cried Jean-Louis, distraught, “there has only been one man of the 32d wounded today, and it had to be by me.”

Seizing upon the incident, the colonel said, “This is a warning; there has been enough blood. All have fought bravely and reparation has been made. Do you trust my judgment in the matter of honor?” After Jean-Louis said he did, the colonel said there was nothing more to do but extend a hand to the 1st Regiment. Pointing to the two provosts who still waited, he said to Jean-Louis, “They cannot come to you!”

Jean-Louis dropped his sword, approached the two Italians, and clasped them by the hands. His regiment cheered, “Vive Jean-Louis! Vive the 32d Regiment!”

Jean-Louis added, “Vive the First! We are but one family! Vive l’armee!”

1816 match between the Comte de Bondy and the fencing master Lafaugere by Frederic Regamey. Jean Louis presided as “President de Combat,” and can be seen at center.

Jean-Louis retired from the army in 1849, at age sixty-five, and began teaching fencing permanently at his school in Montpellier. Later he came to denounce dueling. He instructed his daughter in the art of fencing, and she would go on to become one of his most accomplished disciples.

Arsene Vigeant, a famous writer on fencing, remarked of him “Jean-Louis’ face which appeared hard at first meeting, hid a soul of great goodness and generosity.”

Basile Croquère

During the nineteenth century, New Orleans came to be regarded by many as the dueling capitol of the western world. There, duels were fought more frequently than in any other American city. As to exact statistics, one nineteenth-century visitor noted that “in 1834 there were no less than 365 [duels], or one for every day in the year; 15 having been fought on one Sunday morning. In 1835 there were 102 duels fought in that city, betwixt the 1st of January and end of April.” In 1839, another resident noted “Thirteen Duels have been fought in and near the city during the week; five more were to take place this morning.” Most of these duels were said to have been fought by those of French Creole descent, however, in 1833 William Ladd noted that blacks “are taking it up [dueling]” in the city.

In fact, African Americans fought a large number of duels in Louisiana, which were reported throughout newspapers of the era. One example, published in April 1872 by the New York Times, noted that:

“Two young colored men fought a duel with small swords in New Orleans, on Tuesday, and one was slightly wounded in the breast. One is a son of an internal revenue assessor, and the other a son of a Custom-house official. The quarrel grew out of testimony given before the Congressional Investigating Committee.”Due in part to this prolific dueling culture, the tradition of classical and historic fencing flourished in old New Orleans. From about 1830 until the Civil War, at least fifty maitre d’armes (masters of arms) operated fencing academies in Exchange Alley, from Canal to Conti between Royal and Bourbon Streets. Of these, the author has personally come across six New Orleans fencing masters of African ancestry. Among the most notable of these were “Black” Austin, a free black man, and Robert Severin, also of African ancestry—who fought at least one duel in the city, and served as a second in at least another.

The most renowned of these masters, however, was Basile Croquère.

Croquère, according to Lafcadio Hearn, was “the most remarkable colored swordsman of Louisiana.” For much of the last century, Croquère’s life has been shrouded in mystery, and what is known about him consists mostly of scraps of anecdotal information set down in local histories. What is certain is that he was born in New Orleans around 1800 to a white father and a mother of mixed African-European ancestry.

At a young age, Croquère took part in the War of 1812, and likely participated in the famous Battle of New Orleans (1815)—in which the Americans soundly expelled the British and effectively won the war. In 1879, Croquère was listed as a member of L’Association des Vétérans de 1814-15.

Like the famous St. Georges, Croquère was sent by his white father to be educated in Paris, where he obtained a degree in mathematics, and probably received some, if not most, of his fencing instruction. After completing his studies in France, Croquère returned to New Orleans, where he set up shop as both a fencing master and a staircase builder, in which profession he applied his mathematical knowledge to construct the “soaring, multidimensional staircases” which became the staple of antebellum southern mansions.

By all accounts, Croquère was one of the best masters-of-arms in New Orleans. As one author of the period recounted:

“Though the population could count a considerable number of these fencing experts and duelists, Basile Croquère was proclaimed their superior in all things…He employed his talent to train the youth, to give them the benefit of his skill and his knowledge in arms.”In a city known as the fencing and dueling Mecca of North America, where men literally lived and died by the sword on a daily basis, this was high praise.

“Mr. Basile was an educated and respectable man; he knew how to estimate and consider by his character, his behavior and his distinguished manners.John Augustin (1838-1888), a New Orleans poet, editor, and Confederate veteran, recounted that Croquère “was such a fine blade that many of the best Creole gentlemen did not hesitate, notwithstanding the strong prejudice against color, to frequent his salle d’armes, and even cross swords with him in private assaults.”

It was not therefore strange that a man having these recommendable qualities should enjoy a certain credit among people of high society, in whom he cultivated an elite clientele…

As to his profession of arms, it is told that he could touch his opponent almost as though composing a ballad…He often said that his chest was a holy place: it was filled with air because, we are told, no adversary’s foil was ever able to touch it…”

Although little is known about this extraordinary master, his legend continues to endure among New Orleans guidebooks and books about dueling. Although it would be presumptuous to declare him the greatest of African American martial artists, he was, by all accounts, an extraordinary person and a swordsman of the highest caliber.

Further reading:

Alain Guédé, Monsieur de Saint-George: Virtuoso, Swordsman, Revolutionary: A Legendary Life Rediscovered

Alfred Hutton, Sword & the Centuries

Tom Reiss, The Black Count: Glory, Revolution, Betrayal, and the Real Count of Monte Cristo (Pulitzer Prize for Biography)

Paul Kirchner, The Deadliest Men

T. J. Desch Obi, Fighting for Honor: The History of African Martial Art in the Atlantic World (Carolina Lowcountry and the Atlantic World)

African American Knife-Fighters of Old New York

African American Soldiers fight off 24 Germans with Bolo Knives during World War I

Fencing in Colonial America and the Early Republic

http://sworddueling.com/2010/03/08/jean-louis-michel/

Benjamin Truman, The Field of Honor

This article © 2015 by Ben Miller. All rights reserved. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that credit is given with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Advertisements

%d bloggers like this:

Cheers

Reblogging a great link for Black History Month. I wonder what Stroud-sensei would have thought of this article? He probably would have all their biographies already committed to memory, no doubt.

Swash some buckle!

Great article by Ben Miller.

Trying not to reblog as much, but I couldn’t resist this – it’s awesome!

Very interesting read!

A very nice article about the African Americans fencers.